Is It Propagation or Demolishing to Set Religious Agenda for Oromos?

Jan 03,2022

Introduction

Although there could not be the answer to why religion is an essential topic for Oromos, a political elite attempts to politicize the religious diversity within the Oromo people when they failed to mobilize their people as usual.

This paper will briefly go through the background about the religion of Oromo, conversion to other faiths, and politicization of religion. In the end, it calls for Oromo nationalism and struggles to be secular and neutral of any religion.

What Are the Religions of Oromo People?

The Oromo are Ethiopia's most enormous, ancient, indigenous stock, speaking Cushitic language family (Bulcha, 1995; Sinha et al., 2011). The Oromo histories demonstrate that the Oromo religion was not Christianity or Islam but an indigenous religion known as Waaqeffanna (Kelbessa, 2013; Ta'a, 2013; Aga, 2016; Duibe, 2021). Waaqeffanna believes in a monotheistic God, the creator of the universe and omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent, called 'Waaqa' (Jalata, 2010; Sinha et al. 2011; Kelbessa, 2013; and Aga, 2016).

Ta'a (2013) wrote a Waaqa follower does not require a prophet, saints, clergy, priests, or bishops to worship Waaqa, but instead relies on intermediate spirits known as Ayyaana to do so. The identity and the Oromo worldview consist of three interrelated concepts: Ayyaana, Uumaa (Waaqa's creation), and Safuu (an ethical and moral value that serves as the foundation for human conduct).

Qaalluu Institution

Waaqeffanna is associated with the Qaalluu Institution. Qaalluu (men) and Qaallitti (women) are the earthly protectors of Waaqa laws. Galma is the traditional Oromo ritual hall of the Qaalluu/Qaallitti, while dalaga is the ritual activity of the Qaalluu/Qaallitti. The Muudaa ceremony is the name of the ritual held once every eight years in honor of the Qaalluu. The Qaalluu is also known as the Abbaa Muudaa, the spiritual father of the traditional Oromo faith. Those who visited the Abbaa Muudaa and got his blessings and anointment are Jila. The Jila served as a conduit between the spiritual father and the political system of the Oromo people, Gadaa.

During rituals, Oromo males wear kallacha, a holy religious emblem, while women wear caaccu/callee (beads). Irreecha/Irreessa is a thanksgiving ceremony in which green grass or leaves are presented in river meadows or on mountain slopes. Ekeraa is a belief in life after death in which departed ancestors live as spirits. Ateetee is a women's thanksgiving ceremony.

Are Qaalluu and Qaallichaa Similar?

Legesse (1973) and Knutsson (1967) clearly explained by Ta'a (2013) about the difference between Oromos religious and political institutions and between the Oromo Qaalluu and the Amharic Qaallichaa. The Muudaa pilgrimage is the only meeting site for the Qaalluu and Gadaa systems. So, the Gadaa system was the secular political system. In contrast to the term Qaalluu, Qaallichaa is prevalent across Ethiopia. Only in Shoa and Wollega, the term Qaalluu is associated with a property. In Borana, Qaalluu refers to the few traditional "high priests," but Qaallichaa indicates a primarily anti-social, or at least anti-traditional, ceremonial function. Qaallichaa has a significantly distinct and far lower social rank in Oromo than a Qaalluu. Culturally, Qaallichaa is regarded as alien or somewhat foreign to Oromos (Macha). However, some writers deliberately distorted this fact and associated Qaalluu and Qaallicha.

Generally, Waaqeffanna reflects a feeling of human dignity, equality, and respect. It also encompasses all that is necessary for social interaction and integration. The strong belief in one supernatural force produced a favorable climate for coexistence.

Conversion Of Oromos

Currently, Oromo follow Christianity (Orthodox, Protestant) and Islam, while some Oromos still adhere to their indigenous religion, Waaqeffanna. There are various outlooks among studies on the conversion of Oromos to other faiths. Some said that Oromos completely abandoned Waaqeffanna (Dubie, 2021), while others argued this as the basic tenet of Oromo identity and belief in one God (Waaqeffanna dhugaa) remained (Ta'a, 2013; Gutema and Verharen, 2013) in converted Oromos. However, Waaqeffanna as a religion has been ruined by other faiths.

"It is the unrestrained and unprecedented spread of protestant belief systems which has become a great challenge against the sustainability of Oromo religious practice in the area [Horo Guduru]. This is because this missionary religion is currently snatching out enormous people from the domain of Oromo religion" Sinha et al. 2011, p. 52.

Although conversion of religion may not be problematic, given that individuals have the right to follow any religion they want, it seems that exposure of Oromos to the beliefs of these foreign religions has been affected, Oromo people. The politically motivated expansion of these religions to Oromo people effectively enabled Oromos to give up their Waaqeffanna and to be converted to Islam or Christianity.

Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity

The Orthodox Church became the state religion of Ethiopia until 1974 since its introduction by Ezana in the 4th century AD. It was imposed on the Oromo people by force (Gnamo, 2002; Sinha et al., 2011; Ta'a, 2013; Duibe, 2021). The Orthodox church legitimized the imperial rule of Abyssinian kings over Oromo through Feteha Negest, Kebre Negest and established a feudal Gabbar (serfs) system.

Emperor Tewodros II launched a massive campaign to conquer and convert the Yejju (Warra Sheykh) Oromo to Christianity who had previously accepted Islam. In 1878 at the Borumeda religious conference in Wallo Yohannes IV, the Oromo people accepted Christianity or were expelled in mass. As a result, some of them adopted Christianity, while most refused to accept and fled to Sudan and Southwards in the country. Emperor Menelik II, in his turn, intensified the atrocities begun by his predecessor to some extent increased against Muslims and Oromos (Duibe, 2021; Sinha et al., 2011).

Therefore, Orthodox Christianity deprived of the subjugated people's rights, property, identity, and dignity under this system. Most researchers like Jalata (2010) and Duibe (2021) referred to it as a "Colonization."

Evangelical Christianity

The Church Missionary Society (CMS) was one of Europe's early Evangelical missionary organizations that initiated an evangelical mission to Oromia. The Swedish missionary station was established in Massawa in 1865 when they failed to reach Oromia, and lately, they have succeeded in converting the Oromos into Christianity (Bulcha, 1995; Ta'a, 2013; Gutema and Verharen, 2013; Duibe, 2021).

In 1829, Samuel Gobat and Christian Kugler (preachers from CMS in Egypt) came to Ethiopia to reform the Orthodox Church. Due to his health problem, Gobat was replaced by Johann Krapf, and he met King Sahle Selassie (1813- 1847), ruler of Shawa. Upon the king's refusal, Krapf's explored the living situations of Oromos, including culture, economy, and Afan Oromo (even printed the first translated parts of the Bible into Afan Oromo in 1840 (Duibe, 2021).

The translation of the Bible to Afaan Oromo (the New Testament, by Aleqa Zenab in 1870 and the whole Bible in 1899 by Onesimosnesib) aggravated the conversion of Oromos to evangelical Christianity (Gutema and Verharen, 2013).

Islamisation

The conversion of many Oromos (in Wallo- Raya, Azabo, Yejju, Arsi, Bale, and Bale) to Islam was due to the refusal of Orthodox Christianity and the Imperial rule of Ethiopian monarchs (Gnamo, 2002; Jalata, 2010; Duibe, 2021). The main actors in the conversion of Oromos to Islam were the Muslim merchants.

Islam expanded in Wallagga, Illu Abbaa Boor, and in the Gibe regions due to merchants from Sudan and Egypt.

Between 1875 and 1885, the Turko-Egyptian colonial force compelled the Oromo of Hararghe to adopt Islam. The Adares obtained an intermediate status in the Turko- Egyptian colonial administration.

Politicization Of Religion

Historically, the earliest states were theocratic states that priests or religious leaders ruled. Later on, religious leaders began to give their power to absolute kings or queens until the Renaissance movement and Reformation that brought the principle of secularism.

In Ethiopia, the Orthodox Church retained many lands and owed taxes called asrat under the autocratic rule of Solomonic kings. Therefore, the conversion of Oromos to Orthodox resulted not only in abandoning their religion Waaqeffanna but also in degradation to subjecthood under the Gabbar system.

Similarly, the Ottoman Turks and Egyptians were not peaceful clergies who came with Quraan to the Oromo people in Hararghe. Equally, Islam introduced the Arab and Turks cultural administration "Qaadi" system by devastating the domestic Gadaa system. The Oromos suffered under the colonial rule of Turks until Emperor Menelik brought another feudal administration that replaced the Egyptians and Turks.

Evangelical Christianity was also expanded due to political factors. First, the biography of Onesimosnesib, who played a significant role in translating the Bible to Afaan Oromo, showed political. He has politically left his homeland and sold as a slave. In addition, he was crowned by politician Werner Munzinger (army commander of Egpytian force against Ethiopia and died in Awsa or Afar in 1875). Furthermore, his attempt to teach his people in Afaan Oromo was refused by Ethiopian rulers until 1904. Therefore, even if Onesimosnesib was not a politician initially, these experiences can make him a giant politician.

Second, like, Islam in Wallo- Raya, Azabo, Yejju, Arsi, Bale, and Bale, evangelical Christianity expanded as a refusal to the Orthodox Christianity of Ethiopian imperial rulers. Therefore, we can say that evangelical Christianity succeeded only in areas where their competent Orthodox church was there. Because it is more politically crucial for Oromos than Orthodox as at least preached by Oromos in their language.

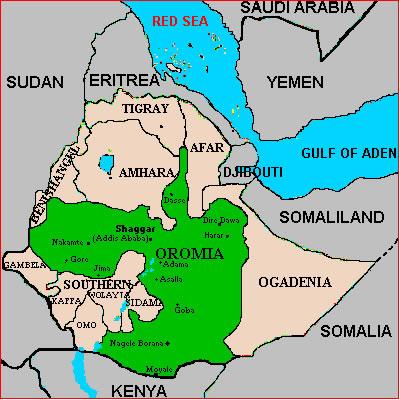

The Oromo Nationalism

Oromo are approximately 40% of the Ethiopian population who share a similar history, speak the same language, live in a defined geographic location, and aspire to a similar political will. Oromo nationalism was revived as opposition to Ethiopian state nationalism that seriously endangered Oromo nationalism in the last quarter of the 20th century.

As shown above, Oromos belong to both Christianity and Islam. Therefore, Oromo nationalism and struggle would be vital if it freed from religion, and let me conclude by Gnamo's quote.

"The roots of Oromo nationalism are not in Christianity and Islam—often reputed, in the Ethiopian context, to be the establishment religion and the anti-establishment religion, respectively. Neither the driving force nor the future political agenda can be religious dogma. Muslims, Christians, and traditional believers fully share the core idea of Oromo nationalism. This would entail that the path of Oromo nationalism is founded on twin policies: secularism and tolerance" Gnamo, 2002, p. 99.

References

Aga, B. 2016. Oromo Indigenous Religion: Waaqeffannaa. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation (IJRSI). III (IV). https://www.rsisinternational.org/IJRSI/Issue26/01-08.pdf

Bulcha, M. 1995. Onesimos Nasib's Pioneering Contributions to Oromo Writing. Nordic Journal of African Studies. 4(1): 36-59

Duibe, N. J. (2021). Oromo's religious conversion in Ethiopia: Historical perspective. Antropoloji, (41), 66-77. https://doi.org/10.33613/antropolojidergisi.798859

Gnamo, A. 2002. Islam, the orthodox Church and Oromo nationalism (Ethiopia). Cahiers d’études Africaines [Online]. (165) 99-120. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.137

Gutema, B. and Verharen, C. (Eds.). 2013. African Philosophy in Ethiopia: Encounter of the Oromo Religion with Evangelical Christianity: A Look at The Meaning of Conversion. Ethiopian Philosophical Studies II. The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy.

Jalata, A. 2010. Oromo Peoplehood: Historical and Cultural and Cultural Overview. Sociology Publications and Other Works. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_socopubs/6

Kelbessa, W. 2013. The Oromo Conception of Life: An Introduction, Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology, 17(1), 60-76. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/15685357-01701006

Sinha, A., Sharma, K., and Mergo, L. 2011. Sacred Forest: Understanding the Cultural and Environmental Worth of Natural Space in Oromo Religion, Ethiopia. Indian Journal of Physical Anthropology and Human Genetics. 30(1-2): 47-64.

Ta'a, T. 2013. Religious Beliefs among the Oromo: Waaqeffannaa, Christianity, and Islam in the Context of Ethnic Identity, Citizenship, and Integration. African Journals Online (AJOL). 8(1). https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejossah/article/view/84373

United States Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services. 1998. Ethiopia and the Oromo People: Is it possible to determine whether an Ethiopian is an ethnic Oromo by the individual's last name? What religion or religions are practiced by ethnic Oromos in Ethiopia. Resource Information Center. https://www.refworld.org/docid/3df0a18e4.html